PART 1 RECAP

If you did not read my last blog post (9/1/21), I shared why traditional Word Walls may not be optimal for children these days–these Word Walls can be confusing (‘the’ under the <t> column when clearly ‘the’ does not begin with /t/, but rather /th/), words which are outlined in ‘frames’ promote visual learning rather than attending to the sounds in words, and are sometimes used instructionally in less than valuable ways. So, what’s a better alternative? Let’s unpack the notion of a Sound Wall. Strap in, it’s a bit more complicated, but unpackable.

A ‘SOUND WALL’…A BIT OF BACKGROUND INFO FOR PARENTS (AND MAYBE SOME TEACHERS)

If you are the parent of an elementary school aged child, you may see what looks to your eye like an ‘unusual display’ of the letters of the alphabet. Even if you are a teacher, it may look unusual to you as well.

The letters are out of order, and the vowel letters may be shaped like a ‘V’. And there are pictures of children’s faces emphasizing their mouths? Letters surrounded by backslashes with different lists of letters? It sure DOES look unusual if you aren’t familiar with the rationale regarding this display.

A Sound Wall is not merely wall decoration—it is best used as a teaching tool, but use of it is highly dependent on understanding why it is useful and how to use it with students.

Let’s back up a minute, well maybe a few years.

When babies learn their native oral languages, did you ever notice they closely watch their parents’ and caregivers’ mouths? Did you ever notice that babies attempt to copy these mouth movements, as well as any hand movements made? Did you ever notice that babies and young children thrive on repetition? I actually think that we all thrive on repetition in one way or another throughout our lives.

Why is this important? Well, these young humans are learning how to produce the various speech sounds, known as ‘phonemes‘, which are combined to comprise the words in their native languages. Speaking involves ‘co-articulation’ of these individual speech sounds and this takes a whole lot of repetition since humans speak in a steady stream.

In order to learn how to read and spell, young children (or children of any age struggling to make sense of print) need to have a concrete awareness (something they can touch and feel) of these speech sounds. New readers and spellers need to have an awareness of how the sounds are put together to make words when learning to read (sound/phoneme blending) and how the sounds are taken apart (sound/phoneme segmentation) when learning to spell. The purpose of a Sound Wall is precisely to provide a concrete awareness of the speech sounds in English.

“The purpose of a Sound Wall is precisely to provide a concrete awareness of the speech sounds in English.”

WHY A SOUND WALL?

A Sound Wall is a way to organize words in a classroom based upon the place and manner of articulation. In other words, think about what it takes in the human brain and facial muscles to orally produce the various sounds (phonemes) of language–we use our teeth, tongues, lips, noses and vocal cords in various ways.

The English language consists of 44 distinct phonemes or sounds:

25 consonant sounds

19 vowel sounds

Numerous combinations (over 200!) of only 26 letters of our English alphabet are used to represent these sounds and make over a million English words!

As Stephanie Stollar of Reading Science Academy states, Sound Walls provide, “a visual support to help students make the connection between the sounds we hear/speak and the letters we read/write.”

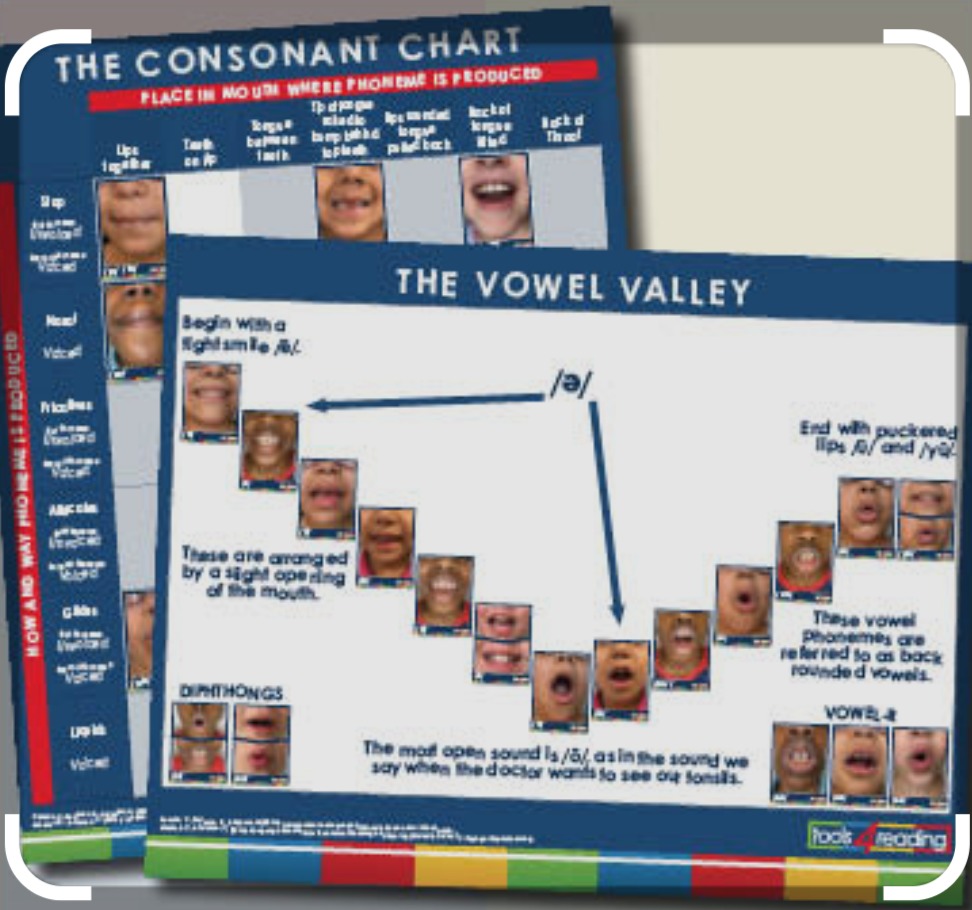

SOURCE: Tools 4 Reading

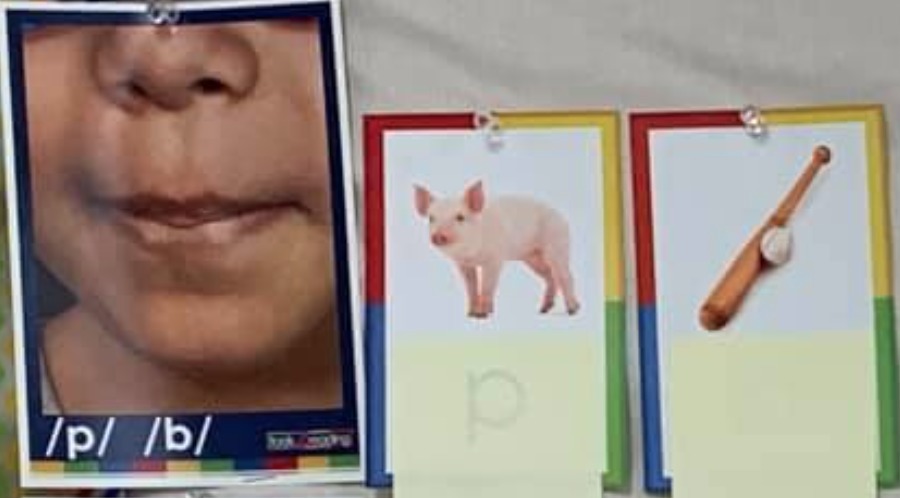

The pictures provide the students with a model of the shape of the mouth and the parts of the inside of the mouth in use when making the different speech sounds. Awareness of the differing gestures can be most beneficial for many students. The speech sounds are written below the various facial gestures, along with a ‘picture’ of a key word beginning with that speech sound.

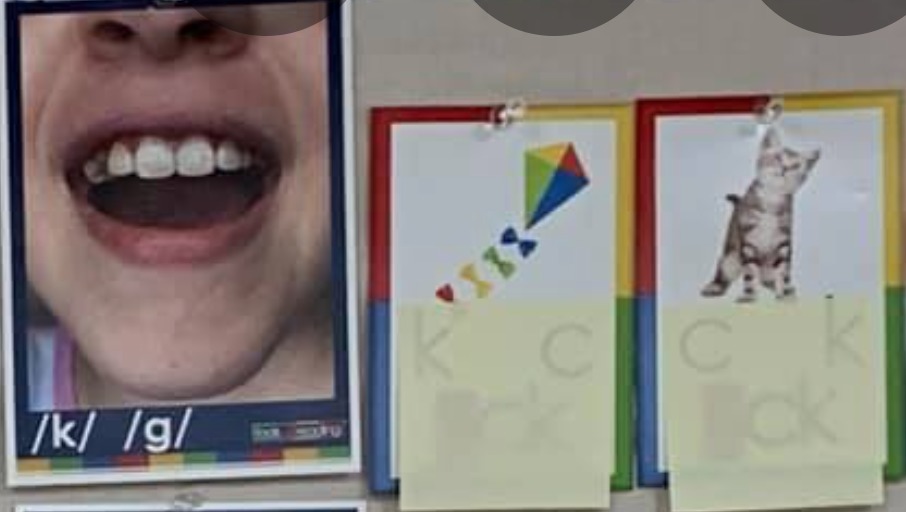

As the various visual letter(s) of these speech sounds are taught, they also may be added to the Sound Wall, so that /k/ would add the spellings of <c>, <k>, and even <ck> as part of literacy instruction.

NOTE: The sticky notes will be removed once the sound and the letter representing that sound have been taught. You can make out the 3 letters/letter combination representing the sound /k/ in the picture on the right. SOURCE: Tools 4 Reading

The consonant sounds are arranged in a specific order depending on where the speech sounds are made in the mouth, moving from the front to the back of the mouth. Adding to this, as is the case with <p> and <b>, the facial gestures are identical–the only difference is that the <p> is simply a “puff of air” without any vibration of the vocal cords (unvoiced) and <b>, also simply a “puff of air”, but does vibrate the vocal cords (voiced). Several sets of unvoiced (no vibration) and voiced (vibration) sound pairings (the facial gestures are identical) exist in English:

The vowel sounds, all voiced or vibrating sounds, vary in terms of the position of the jaw and the mouth–in other words–how far apart the jaw is open, with the short /ŏ/ at the bottom of the valley where the mouth is open farthest.

This approach favors the perspective of the learner rather than the perspective of the teacher. That said, it is my thought that Sound Walls provide additional cues to the teacher (and/or parent) when working with students/children. Sound Walls remind us to:

1 – model consonant sounds clearly without adding an additional schwa /ə/: /b/ rather than /buh/, /l/ rather than /luh/

2 – note and talk about the various mouth movements, positions of the teeth, lips, tongue, and air flow from their mouths and noses–and have students feel their throats (vocal cords) to check for voiced vs. unvoiced speech sounds

3 – increase awareness of the various letter combinations used to represent sounds in written form (spelling options)

4 – note that <qu> and <x> are placed ‘off to the side’ near the /k/ phoneme on Sound Walls since each of these grapheme(s) is made up of 2 phonemes <qu>=/k/../w/; <x>=/k/../s/. Do note the first phoneme in both <qu> and <x> is /k/–children will need direct instruction from teachers and parents to understand why <qu> and <x> represent two phonemes and thus 2 different mouth positions consecutively.

I am reminded of a fifth grader I worked with years ago as a literacy coach. He mispronounced, misread, and misspelled words with /f/, /th/, /v/. I spent a little time with him showing him the similarities and differences between these 3 phonemes. We used handheld mirrors so that he could look at my facial gestures while he looked at his own. He felt his throat to check for vibration. I modeled, we practiced, and then he practiced independently. At the end of what was just about a 10 minute mini-lesson, his one and only response was, “no one ever showed me this before.” This took place well before the development of Sound Walls and perhaps this misperception could have been avoided had he been taught the variations of speech sounds as a primary student. Although I cannot tell you that all his literacy issues were solved that day, his response resonates.

DIFFERENCES DEPENDING ON THE STUDENTS’ AGES?

The basics of a Sound Wall are pretty much the same no matter the ages of the students.

It is recommended that individual sounds should remain ‘locked’ (covered–a sticky note will do just fine) until the individual sounds have been directly taught, at which point these sounds are ‘unlocked’ by removing the sticky note.

As more spelling patterns are taught, they should be added. For example, the /k/ phoneme at first would list <c> and then <k>. Once the most common <ck> pattern has been taught (use at the end of a 1 syllable word after a short vowel as in ‘sock’), the <-ck> would be added. When students are older/more advanced, they will have been taught many, many spelling patterns for the 44 phonemes–particularly the vowel phonemes–and these will be listed as they are taught.

Do I think labels such as stops, fricatives, affricatives, glides, nasals, liquids (note these labels on the pictures of Sound Walls above) should be taught to all students? Although I am not a Sound Wall expert, I believe all children should have at least exposure to these terms, and especially older students who need to learn this information enjoy learning the more sophisticated terminology. Do adults need to master these labels? It is also far more important that adults understand and reference these labels with application when teaching than simply memorizing each label. This allows students, teachers, and parents a label which matches what their mouths are doing. Many Sound Walls displays have pictorial representations as you can see on the right, which provide additional visual cues for both students, teachers, and parents.

Source: LiPS

TEACHER BACKGROUND/UNDERSTANDING NEEDED

As my colleague, Sheryl Ferlito, adeptly points out in her recent blog, it is important for both teachers to understand the speech to print basis of reading prior to tackling implementation and instruction using a Sound Wall–this may take some time. Both teachers (and parents) can learn more about Sound Walls and pose questions to the experts at Tools4Reading as well as check out a weekly blog post. Teachers (or parents), you can enroll in virtual Sound Wall Classes, and purchase Sound Wall Solutions, which contains everything needed to begin to implement a Sound Wall. There are even materials for use at home including Student Sound Wall Folder, a Poster Set, and an At-Home Teaching Pack, so no need to ‘reinvent the wheel’ if you prefer. Author Dr. Mary Dahlgren is an expert, making Tools 4 Reading a vetted and valued resource. Trust this source, as well as the support of the school speech/language pathologist rather than what you may read elsewhere on the internet.

Teachers, I suggest you use your Sound Wall as part of your daily decoding/encoding instruction–it is not intended as a ‘stand alone’ instructional piece. Parents, I suggest you follow the lead of your child(ren)’s teachers even though I suspect some parents out there want to utilize these resources independently of what/how literacy is taught in the classroom. Asking questions such as: “Where is your tongue when you make the /th/ sound?” or “Is the sound of /t/ voiced or unvoiced?” will undoubtedly enhance your instructional objectives as they relate to your phonics instruction–and thus, improve children’s literacy..

HOW TO HELP YOUR CHILD AT HOME

Parents, the more you know about how literacy develops, the better you can support your child(ren). Partner with your children’s teachers if they are using a Sound Wall. Don’t be afraid to ask questions such as: “How do you use the Sound Wall during instruction?” or “Can I take some pictures of your Sound Wall so I can reference it with my child at home?” (BTW, I hope this article helps!)

Given that many school districts have mask mandates, having Sound Wall articulation pictures provides both you and your children with gestural ‘anchors’ of our English speech sounds, which can be practiced and applied when reading/spelling in the safety of your homes. According to Educational Psychologist, Linnea Ehri, the actual process of articulation and pronunciation interact with children’s abilities to form sound-letter connections, which then bond and are connected with the spellings and meanings of words to be learned. You can even create your own articulation pictures by taking pictures of your child with your cell phone to recreate the Sound Wall that may be posted in the classroom. Using handheld mirrors or any mirror is most beneficial when practicing.

Consider Sound Walls as evolving over time to help meet the needs of the child as he/she builds a reading brain. Do you have questions and/or comments? I am ‘ALL EARS’!!

Hi Lori – Excellent and so teacher and parent friendly! Di

Di, It’s the goal!! Share with who you think would benefit! LJ