Question Posed: How can I help my child learn to spell?

Part 2 – Early Elementary Students (and beyond if necessary)

As I reread last week’s post, I realized that it was long, heavy on theory, and easy for folks to get ‘lost in the sauce’–time to unpack some of the information.

So, for this week, I suggest you reread my post from last week and then enjoy some ‘meat and potatoes’ to help your child learn how to spell–sorry if you are a vegetarian!

Before being able to learn to spell a list of words or write a story, students need to be able to:

1 – ‘hear’/’distinguish’ the speech sounds of the language they use in school and are attempting to learn to read and spell

2 – spell these sounds at the ‘sound level’. That means students would benefit from having individual sounds dictated in isolation–just the sounds–maybe 5-8 for each practice session. For example, if an adult dictates /b/ (those backslash marks indicate the sound of the ‘b’ rather than the letter name), the student should then write a ‘b’ and state the letter name. It is ‘a must’ that students learning to spell in English be able to distinguish between the short vowel sounds in isolation since nearly half of English syllables contain short vowel sounds. Please do include these in your practice. Short vowel sounds are typically shown this way: /ă/, /ĕ/, /ĭ/, /ŏ/, /ŭ/. That little symbol above the letters is called a ‘breve’ and appears in dictionaries to help readers pronounce unknown words. The breve tells readers the vowel is short.

The issue in English is that many of the sounds (or phonemes) are represented by many different letters and/or letter combinations. That’s when this gets tricky. So if a student is asked to spell /k/, the correct response would be: c, k, ck. When to use which one? There are generalizations (not ‘rules’) to teach even to elementary children, but students of all ages would benefit.

Then there are the long vowel sounds, typically shown this way: /ā/, /ē, /ī/, /ō/, /ū/ as in ‘cute’, and /ǖ/ as in ‘flu’ (did you know there were 2 long ‘u’ sounds?). The little symbol (the horizontal line) above the letters is called a ‘macron’, telling readers the vowel in question has the long sound. The little symbol above the second long ‘u’ sound is called an ‘umlaut’, telling readers the vowel in question has the long sound of ‘u’ as in ‘flu’. When a child is first learning to read and spell, and asked to write down the letters representing the /ā/, he may respond with: a, ai, ay at first, but in fact, other representations include a-e (Vowel-Consonant-e pattern as in ‘name’), ‘ei’, ‘a’, and ‘eigh’. These last 3 options are far less common and are learned gradually as a student internalizes the more common spellings for this very common sound (long /ā/ as in ‘name’).

Students of any age who need help with spelling benefit from practice at the sound level. Students who have not yet mastered the consonant sounds (including the digraphs ch, sh, th, wh) and short vowels benefit from mastering these first before moving on to more complex long vowel sounds and other combinations. The video 44 Phonemes helps parents and children by showing the correct mouth formations and sound production of the phonemes used in English.

3 – spell at the word level by being able to ‘notice’ and then ‘hold in memory’ the sounds in the correct order…then be able to encode–or spell–these sounds in sequence by stating the letter names and writing the letters down either on a whiteboard, paper, chalkboard, etc. If a child has difficulty ‘holding’ single syllable 2 and 3 sound words in memory, it only makes sense that it would be difficult for the child to ‘hold’ longer single syllable words with 4, 5, or 6 sound words (for example, ‘flag’-4 sounds, ‘splash’-5 sounds, ‘sprint’-6 sounds, etc.) in memory in order to be able to spell them. Words with more than one syllable can be practiced as well. Students need to be able to orally say the words in discrete syllables and then repeat the procedure described at the beginning of this section (for example, ‘cabin’ would be broken down into /căb/-/ĭn/, or /hŭn/-/drĕd/). As you can see, new skills are dependent on earlier learned skills.

Students of any age who have not yet mastered the ability to ‘hold’ single syllable words in memory and then spell them would benefit from practice at first the 3, 4, and then 5-6 sound level. Once students have mastered these skills, they can proceed to words with 2 syllables. Asking students to simply ‘memorize’ lists of longer words visually does not allow them to understand sound-symbol relationship, typically resulting in great effort with little payoff. As students master short vowels, the long vowels are introduced, as well as the many other combinations including r-controlled vowel sounds (/ar/, /or/, /ər/), suffixes, and more advanced combinations such as ‘tion’ and ‘sion’ with lots more choices for the correct spelling. The point here is this: You can best help your child by working on more common combinations first. Spelling is a process and improvement takes time.

For the High Frequency non-phonetic words, please do review my previous blog post outlining best practice.

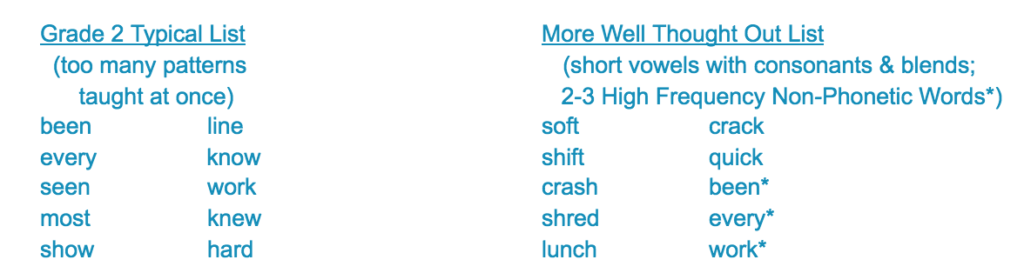

Let me share with you a typical spelling list containing too many patterns as compared with a more well thought out plan:

What’s The Goal Here?

Application of a student’s knowledge at the sound, word, sentence levels, and ultimately at the written language level is the goal. Students need to have practice ‘holding’ several words in memory, while attending to spelling each word, sequencing the words, using correct letter formations, and paying attention to the conventions of capitalization and punctuation, while at the same time keeping their ideas in mind. It’s a juggling act for sure.

Start with short sentences using the words with the concepts worked on and build up to longer sentences. While this can occur naturally and easily for some students, it is often quite challenging for others. Please do supply your children with lists of High Frequency Non-Phonetic Words (words such as ‘go’, ‘to’, ‘the’, ‘said’, ‘could’, etc.), so they can reference these lists in favor of guessing and repeatedly misspelling these words. It is perfectly fine to help your child spell these words when composing, as well as phonetically regular words (words with good sound/symbol relationships) containing concepts they may not yet have been directly taught and/or mastered.

Again, spelling mastery takes time.

The idea is for your child to express their thoughts in written form–we can always go back and work on the spelling later. This is old fashioned ‘proofreading’–and it is a skill we need to practice with children. Even children who have no difficulty reading, spelling and writing would benefit from direct instruction with proofreading. I would consider it a ‘life skill’. Any blogger would tell you they proofread their writing prior to hitting the ‘publish’ button.

You Ask About Letter Reversals and Articulation Issues?

What about letter reversals? This is ‘normal’ skill development, especially in young children. I have found that the best way to correct these is to teach children the correct letter formations. Students learn these best by tracing, copying, and then writing from memory. I can make recommendations for help here if you reach out to me in the comments section.

What about students with articulation issues and students who mispronounce words? Most of the time, these issues will resolve or a student may need a speech/language referral, evaluation, and speech therapy. Although some students may mispronounce words, they are aware of the correct pronunciation and spell correctly. The sound /r/ and /l/ are typically the last sounds mastered and many students can correctly spell words such as ‘like’ and ‘ran’ even if their articulation is unclear. For others, mispronunciations show up in their spelling. For example, ‘with’ could be spelled as ‘wif’ (f/th issue) or ‘going’ spelled as ‘goin’ (omission of the final /g/. In students a bit older, the common word ‘recognize’ is often pronounced as ‘recunize’ and I find it is often misspelled, as is the common word such as ‘practically’ (spelled ‘practicly’)–these students sometimes have deficits even at the sound level.

My Top 3 Suggestions For Parents! And Remember, Spelling Is A Process Learned Over Time!

1 – Pay attention to the types of spelling errors your child makes so you can figure where the breakdown is occurring: sounds? (sound omissions, substitutions, incorrect letter combinations selected), non-phonetic high frequency words?, too much time needing to study?, legibility? (sometimes children will purposefully provide two options of a spelling within one word).

2 – Some children limit their writing to only those words they feel comfortable spelling. If you feel your child’s oral language far outpaces their written language, difficulty with spelling may be at the root of the issue and should be addressed.

3 – Monitor your child’s level of frustration (perhaps your level of frustration as well!)–speak with your child’s teacher as is necessary–and provide supports as you can in the form of technology (Siri, Alexa, Spelling and Grammar Check), lists of commonly used words in writing, speech to text as needed (but be very careful that your child also learn to write conventionally), and most importantly, make proofreading a necessary and routine part of the process. Remember, writing each word several times and simply trying to ‘memorize’ for a Friday test is not the way.

Have a particular need or question? Just ask me.