I came across a question posed this past week to the increasingly popular FaceBook Group called Science of Reading–What I Should Have Learned In College (SORWISHLIC):

What is the history of Science of Reading (SoR)?

A poster’s question from Science of Reading-What I Should Have Learned in College

First, a little about the FaceBook Group

My friend and colleague, Donna Hejtmanek, a retired teacher, started this group in August 2019 out of frustration with what she experienced, heard, and saw over her many years in the classroom (Donna’s own words).

Today, not even 3 years later, the group’s numbers have swelled to nearly 200,000 members. The group composition includes teachers, administrators, university faculty, researchers, parents, and other concerned citizens.

Most members are willing and eager to learn more about literacy–more specifically, how to better reach and teach the students and/or children under their charge. How can they make learning to read and spell easier for those in their classrooms or learning in their home environments? In fact, many had never heard the term ‘Science of Reading’ until recently. The SORWISHLIC Facebook Group routinely offers webinars, ongoing professional development, free information/resources, as well as a forum for discussion moderated by literacy experts. Kudos to my colleagues (myself included) who volunteer their time to respond to each and every post received, responding to questions big and small in a positive and timely fashion.

Teachers bear the responsibility of teaching their students how to read and spell proficiently across the grades. Even though teachers bear this responsibility, many, if not most teachers, do not have the freedom to choose the approach and specific curricula. This choice is typically that of school administrators.

To this day, undergraduate students studying to become teachers often take classes which do not prepare them to teach literacy skills most effectively and efficiently. Even teachers pursuing graduate degrees have shared with me that they learned little in their coursework helping them learn how to teach literacy skills more effectively and efficiently.

This is a societal conundrum, especially since literacy scores remain so low in our country.

The success and expansion of this FaceBook Group, as well as the many offshoots (SoR Grades K/1/2, SoR 3rd Grade and Beyond, SoR for Middle School, SoR for Parents, SoR for Administrators, statewide SoR groups, SoR Writing, etc.) speaks volumes in terms of the veracity of this hunger for knowledge on the part of all stakeholders.

For those of you who have not heard about education journalist Emily Hanford’s work, check it out here. Ms. Hanford has further propelled the success of the grassroots movement based upon Science of Reading.

Back to the History of Science of Reading: What is ‘New’ is Really ‘Old’ (1936)

I was one of those teachers who attended graduate school and never really learned how to teach reading and spelling to my students and why it was important to know this information until I left full-time classroom teaching after five years, stumbled upon a knowledgeable group of educators, and became involved in what was then The Orton Dyslexia Society (now The International Dyslexia Association).

It was then–and I am talking over 35 years ago–that I learned how a human being’s development of oral language and therefore thoughts can be coded into written symbols representing those same thoughts. These thoughts remain and can be shared due to this written code of oral language.

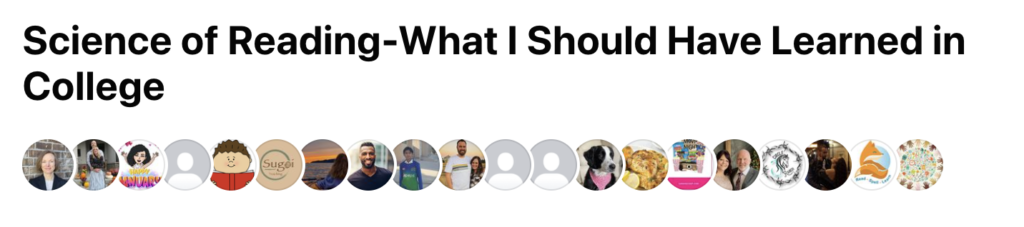

Here is one of those pictures that is worth 1,000 words. It comes from The Gillingham Manual, first published in 1936!

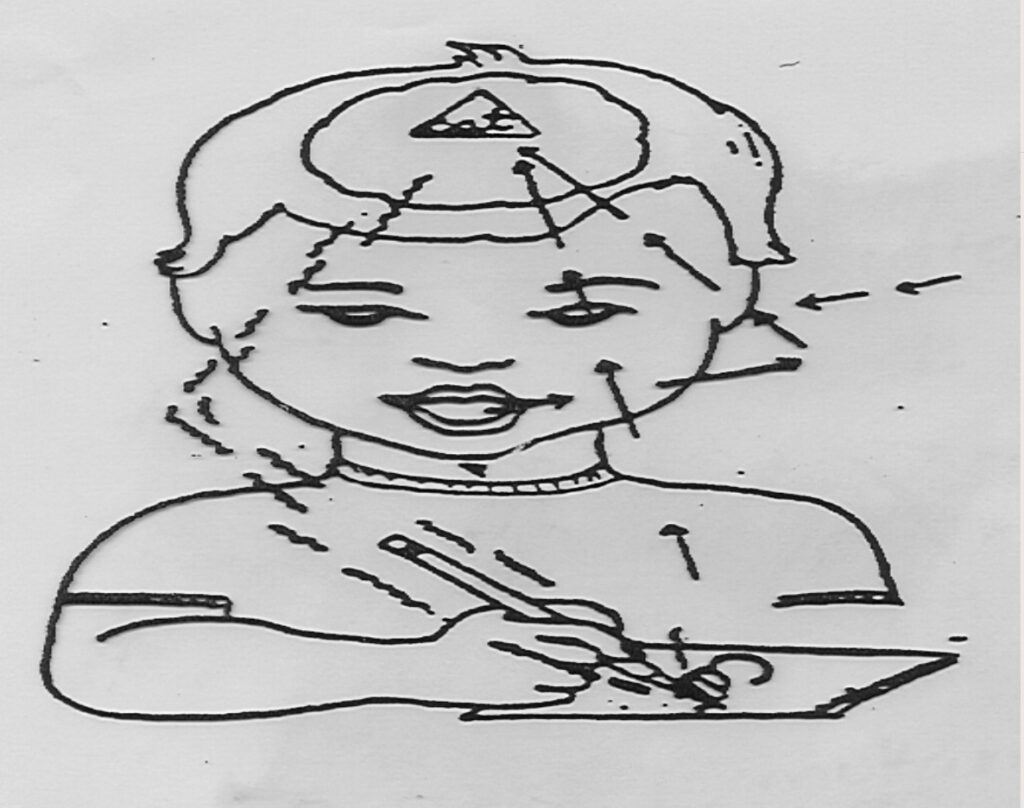

This is an infographic explaining the picture, also published in The Gillingham Manual in 1936.

When a child is taught literacy by hearing a word, saying that same word, seeing that same word, writing that same word, they have a better chance of learning that word–that is, if they have been taught:

- the sound/symbol associations of the sounds/letters in that particular word (phonics)

- how to blend the individual sounds in that word for reading

- how to segment the individual sounds in that word for spelling

- how to execute the correct letter formations needed for writing these letters (handwriting)

This approach was the brainchild of neurologist Dr. Samuel T. Orton, who began working with psychologist and educator Anna Gillingham and educator Bessie Stillman in the 1920s and 1930s. Their approach was designed to help individuals who had difficulty learning to read and spell in the early part of the 20th century. These individuals were thought to have dyslexia. Of course, little was known about how the brain specifically processes the written code of English. That said, Dr. Orton and his colleagues had targeted the precise ‘linkages’ (his term) that need to be in place between the visual, auditory, and kinesthetic (movement) brain processes.

The thought behind the Orton and Gillingham approach involved organizing the English language into a precise scope and sequence moving from the simple to the complex, as well as the most common patterns to the least common patterns. Therefore, the language could be taught more systematically and directly for both reading and spelling targeting individuals with dyslexia.

As a result of many decades of research examining how the human brain processes both oral and print language, we know with far more specificity about how literacy develops. We also know that although humans possess hard wiring for oral language, reading and spelling do not develop naturally. We also know that every human goes through the same processes when learning to read and spell; the development of new neurological pathways are necessary to connect the visual, auditory, motor, and linguistic areas of the brain. We have cognitive scientists Stanislas Dehaene, Mark Seidenberg, and Mary Anne Wolf, amongst others, including literacy expert Louisa Moats, to thank for this knowledge base.

Now we know that Dr. Orton, Anna Gillingham, and Bessie Stillman were correct—but—and it’s a BIG but. The methods they developed for individuals with dyslexia are the very same methods most beneficial for all readers and spellers. That is, not just for students with dyslexia and/or other learning differences.

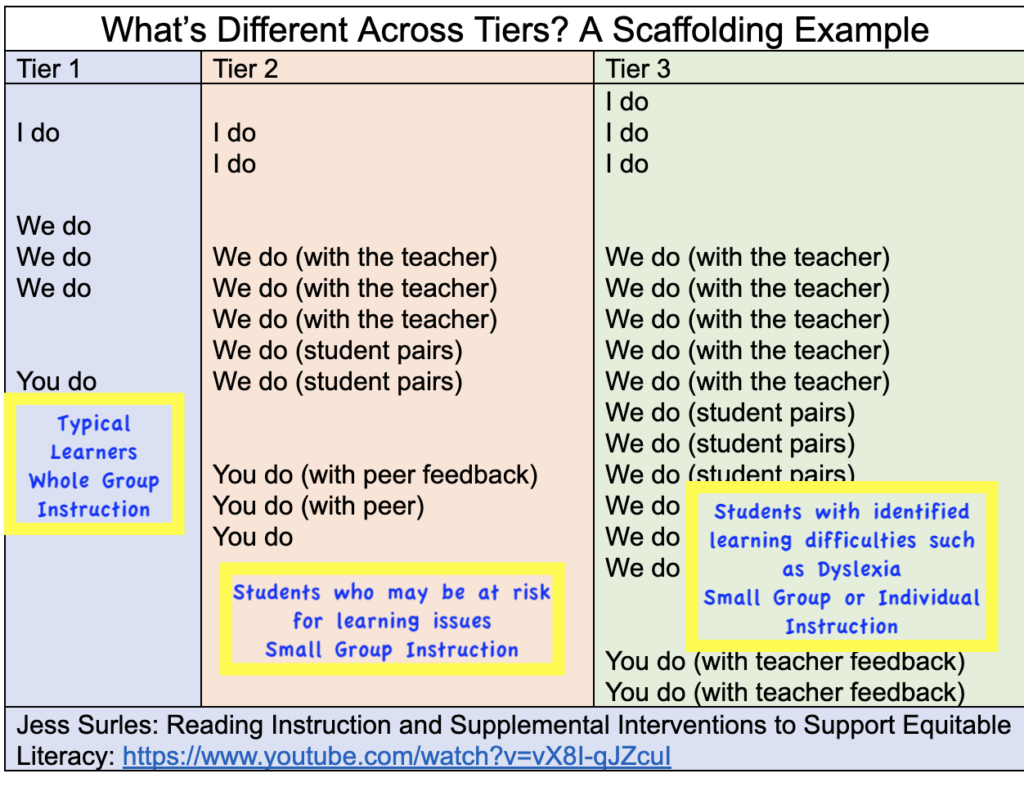

The infographic below helps us to understand that students need to learn the same information; however, learners are different and require different numbers of repetitions with varying teacher modeling and guidance. Thanks to Jess Surles for this infographic. The yellow boxes are my additions explaining which groups of students are targeted for various quantities of practice and guidance.

Science of Reading tells us how the brain learns literacy, as well as why it is important to have this knowledge base. Science of Reading tells us the various tenets of what needs to be taught based upon Gough and Tunmer’s Simple View of Reading (1986), the 2000 National Reading Panel, and Hollis Scarborough’s 2001 Reading Rope. Very simply put, these are:

- phonological awareness

- phonics

- fluency

- vocabulary

- comprehension

Along with the various FaceBook SoR Groups, organizations such as The Reading League (TRL) offer information to the public about the Science of Reading. TRL’s Science of Reading Defining Guide is a free download outlining the definition of SoR, the components of scientifically based research studies, an explanation of how reading is processed in the brain, an overview of the components of word recognition and language comprehension needed to attain literacy, and instructional practices aligned with teaching these same components of word recognition and language comprehension.

This information is at your fingertips–literally–just at your keyboard, tablet or phone.

What we need to know has been known for a LONG time even though it has relatively new branding and has attracted increasing publicity. It’s time to learn for yourself whether you are a parent, teacher, administrator, or concerned citizen. Share your knowledge with others. Our students and children depend on it. Our teachers depend on it. The future of our world depends on it.