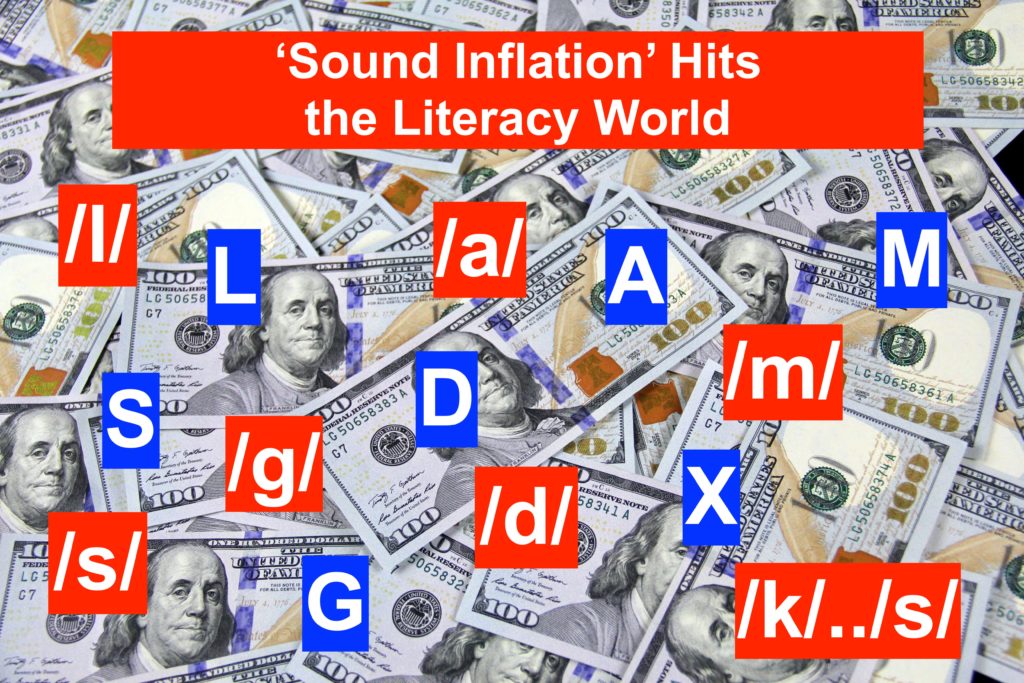

INFLATION HITS THE LITERACY WORLD

Has anyone reading this article NOT noticed the unprecedented rates of INFLATION hitting the nation? Highest levels since 1981! Everything from food to gas to airline prices to the housing market..and yes, to even discussions about how young readers should be taught.

Is it best to teach the letters of the English alphabet first OR is it the sounds of our English language first???

According to Investopedia, “inflation is a decrease in the purchasing power of money, reflected in a general increase in the prices of goods and services in an economy.”

The only issue is that what we know–and I mean the big ‘we’ inclusive of researchers, teachers, administrators, as stakeholders–continues to change, resulting in discussion, confusion, and lack of consensus. Currently, the ‘buzz term’ is “Science of Reading”.

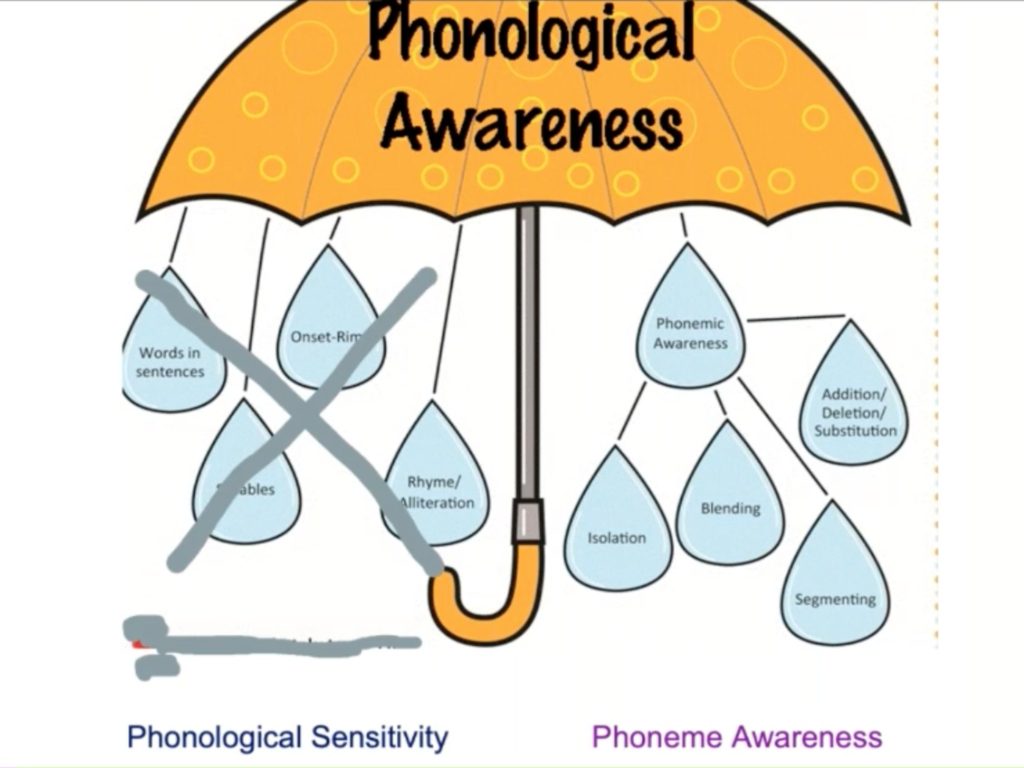

30 years ago, in the 1990s (researchers have been working on this for 50 years!), the ‘buzz term’ was Phonological Awareness–one’s awareness of and the ability to manipulate sounds in oral language. This includes the perception of the individual number of words in spoken sentences or individual speech sounds in words, amongst other oral manipulations of individual speech sounds. The correlation between one’s phonological awareness and ability to access print (read and spell) remains high. There is no doubt of that, but….how much is too much?

Don’t get me wrong–I am all about the Science of Reading (SoR). Why? Because SoR helps stakeholders understand the processes taking place in the human brain enabling new neuronal connections to be formed when learning to read and write–in other words–to become literate. If you are unfamiliar, click here and learn more about it.

Back to INFLATION…Have stakeholders who hold firm to large segments of instructional time devoted to strictly oral phonological awareness exercises causing ‘Sound Inflation’ at the expense of using those precious and limited literacy instructional minutes to improve actual student reading of words/text and spelling of words/written language?

When teaching foundational reading skills to our younger kids and/or older struggling readers, we must think about getting the ‘most bang for our buck’–yes, pun intended!

In other words, are teachers/parents spending too much time working with kids on oral sound manipulation? Are we ending up with students who may have actually read and spelled more quickly and at higher levels had more time been devoted to working on the connections between oral language sounds (phonemes) and letters (graphemes)? Is it possible that more time could be devoted to other aspects of language learning including spelling (known as ‘orthography’), vocabulary, comprehension, and background knowledge?

Turns out that becoming literate is pretty darn complex. Click here to read Louisa Moats’ seminal article entitled “Teaching Reading is Rocket Science” for more on that.

I can tell you for sure that the integration of language sounds with written print is a must–and the sooner the better. Susan Brady’s most recent webinar, Rethinking Instruction in Phonological Awareness: Focus on What Matters! emphasizes this notion, stating that the most important skills emergent readers need are blending individual phonemes into words in order to decode, and segmenting words into their individual phonemes in order to spell using letters. This instruction takes precedence over oral practice with larger units of speech such as syllables, counting words in sentences, and even detecting and producing rhyme. Children do not need to master larger units of speech before moving to the level of the phoneme. Furthermore, she spoke of the benefits of “integrating phoneme awareness with letter knowledge and handwriting.”

Image from Susan Brady, Rethinking Instruction in Phonological Awareness: Focus on What Matters!

SOUNDS FIRST OR LETTERS FIRST?

Babies from birth, and toddlers, just naturally ‘tune in’ to oral language—and guess what else? They tune into the print that is our English alphabet as early as the age of 18 months. Receptive (listening and understanding) and expressive (speaking with purpose) language typically blossoms between the ages of 2 and 3 years of age. Two year olds are in the ‘naming stage’ of language development–and want to know the ‘names’ for everything–including letters.

Parents just naturally share their children’s names and the letters that make them up. Parents sing the “A, B, C Song”. Children are exposed to ‘alphabet books’ right from the very beginning when parents, daycare providers and/or librarians engage in read- alouds. Many 3 year olds recognize the spellings of their own names and are fascinated with “STOP” signs.

Should parents, caregivers, preschool teachers continue to play with oral language?? Yes, ABSOLUTELY! Keep it up!!

BUT…Educators cannot ‘unring the bell’ of the prior exposure of children to the names of the letters of the alphabet upon entrance to kindergarten or even upon entrance to preschool.

“Teaching phonemic awareness without orthography [the print] is just wrongheaded.”

-Dr. Kathleen Brown, Director of the Reading Clinic The University of Utah

Emphasize that the printed letters represent the sounds of our spoken language, and that we put these sounds together in sequence to represent words bearing meaning in our spoken language. This is very different from stating something like: ‘b’ says /b/ since letters don’t ‘say’ anything. This is known as ‘The Alphabetic Principle’. For a deeper dive into the bootstrapping of letters (print) and sound, I encourage you to listen to Dr. Brown speak on the most recent Teaching Literacy Podcast: Reviewing Kindergarten Phonological Awareness Materials.

Be on the lookout for the many confusions since some of the names of the letters do not ‘match up’ to their most frequent corresponding sounds including: ‘c’ (the most common sound/symbol relationship is /k/ as in ‘cat’, ‘g’ (the most common sound/symbol relationship is /g/ as in ‘girl’). The following letter names do not ‘match up’ to the sounds they represent including ‘f’ (name of the letter is “/ĕf/”, ‘h’ (name of the letter is “/āch/”), ‘l’ (name of the letter is “/ĕl/”), ‘m’ (name of the letter is “/ĕm/”, ‘n’ (name of the letter is “/ĕn/”, ‘r’ (name of the letter is “/ar/”), ‘s’ (name of the letter is “/ĕs/”, ‘w’ (name of the letter is ‘double u’–the reason is this: in the early days of English, the letter was actually a double u–like this: uu!–who knew?), ‘y’ (name of the letter is “/wī/.

Let’s not forget the doozies of ‘q’ and ‘x’, both of which actually represent 2 phonemes (speech sounds). The name of ‘q’ is “/kū/”, while its most frequently occurring corresponding phonemes are /k/../w/. The name of the ‘x’ is “/ĕks/, while its most frequently occurring corresponding phonemes are /k/../s/. Who wouldn’t be confused, let alone a 6 year old??

Unbelievably, half of the letters in the English alphabet have the potential to cause confusion in terms of sound/symbol relationships. And let us not forget that the English vowel letter names (a, e, i, o, u) only provide a clue to the long vowel sounds—when in reality, the short vowel sounds (as in ‘cat’, ‘edge’, ‘itch’, ‘octopus’, ‘up’) are far more prevalent in English syllables.

No wonder! Don’t say I didn’t tell you learning to become literate is complex!

THE TAKEAWAY

What are parents to do? What about teachers?

I cannot tell you how many older students, even in middle and high school I had both the joy (my pleasure to help these students) and the sorrow (due to their often needless literacy challenges) of working with over the past 4+ decades who still were unable to identify the sounds of the letters causing confusion. Routinely, responses were ‘q’ = /k/ (this is correct, but not the most common sound) or /kū/, ‘r’ = /ar/, ‘w’ = /d/, ‘x’ = /k/ or /ĕ/, and ‘y’ = /w/ due to students’ incorrectly using the initial phoneme (sound) of the letter name. Many of these students were never taught the distinction between the letter name and the speech sound(s) these letters represent. Most, when taught, stated, “Why didn’t anyone ever tell me that?”

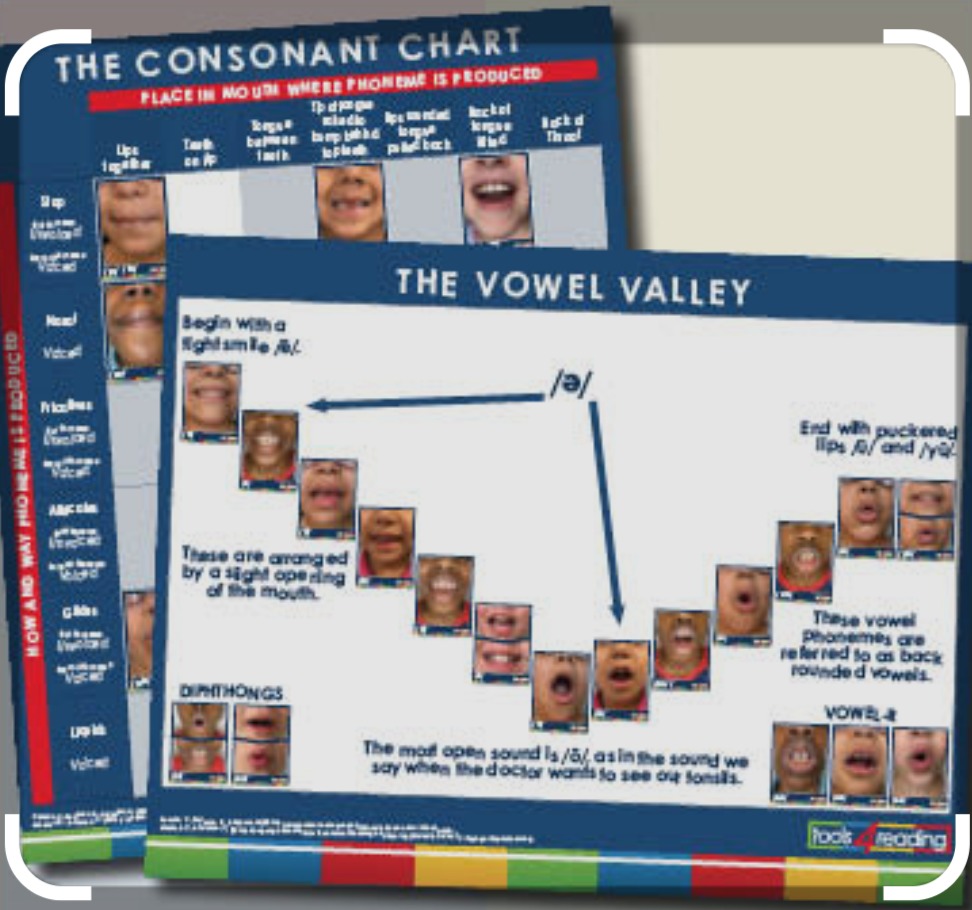

Thus, emphasizing ‘sounds’ is great, and I applaud those educators and parents using mirrors, pictures of students’ mouths, and ‘whisper phones’ when articulating the individual sounds of our language. The recent emergence of Sound Walls emphasizes this focus on speech sounds (mouth formations, slight differences between speech sounds, etc.). I encourage you to read my colleague, Sheryl Ferlito’s, piece on Sound Walls, as well as my past blog posts (Part 1) and (Part 2) on the same topic.

While emphasis on ‘sounds’ serves to reduce the confusions I describe, it is imperative that speech sounds be tied to and integrated with the print representing these sounds. The sooner the better. That’s because reading and spelling function using print.

Maya Angelou’s famous quote appears appropriate to share at this point:

Let’s think about what our kids really need (both at home and at school) and do better.

Let’s curb ‘Sound Inflation’ and include the connection of sounds to print (and vice versa print to sounds–it’s a two way street) ASAP.

Well done Lori!

Thank you

Excellent article Lori!!!

I loved the way you connect the current situation of inflation to the way educators have been focusing on Phonological awareness.

Naama,

Glad you appreciated the insights. Please share this article with your colleagues–too many kids are sitting through too many oral phonlogical awareness activities these days. This is especially true for Tier 1 kids!! PHONEMIC awareness is where it’s at!! Blending, segmentation in tandem, along with letter formations.

Cheers,

Lori

Great Article

“Sound Inflammation” describes a weakness in our literacy practices.

This article is one I will share with colleagues & parents.

Agree! Adding, too, that advanced phonological awareness skills do not magically transfer to reading words. I witnessed a 10 minute PA lesson in a public school that included some complicated deletion and substitution tasks. When I sat down to read with the children, they couldn’t blend CVC words! Showing them how to do so (took about 10 minutes) unlocked that mystery!

Jill,

Right you are! I have witnessed and experienced likewise. I think that teachers have grasped onto the all-in-one, scripted programs emphasizing oral PA far too enthusiastically. The kids who don’t really need all that much practice love it; the kids who have difficulty do NOT love it, and many of them respond a millisecond later than the kids who don’t need it, thus ‘fooling’ the teachers who think it has done wonders with their students. I do not understand the reason for such a wide embrace of oral PA as if it is the magic bullet that will create readers. Thank you for taking the time to comment.

Lori

Really clear website , thanks for this post.

Thank you for your kind words–please share with others.

Lori