A question from a teacher this week prompted this article. The teacher writes:

I tutor a 9 year old student with a diagnosis of dyslexia. This student has been taught ‘the code’ (I take that to mean this student is familiar with most, if not many sound/symbol relationships). This student’s first or ‘cold read’ is 60 wpm, and then when this student rereads the passage a second time, this student reads 100 wpm. The question is: How can I get this student to 100 wpm the first time the passage is read?

LET’S DEFINE THE TERM…WHAT IS FLUENCY?

Simply, the term ‘fluency’ can be defined as reading connected text with speed, accuracy, and expression. In other words, when reading aloud (or even silently), readers should be able to read the printed words quickly, accurately without conscious and methodical attention to the mechanics of decoding or sounding out each word, while mimicking the pace and rhythm of spoken language. According to Joan Sedita, “Fluency combines rate, accuracy, automaticity, and oral reading prosody (expression), which taken together, facilitate the reader’s construction of meaning.”

How a reader chunks words in meaningful phrases and attends to punctuation to enhance meaning plays an important role, as does a reader’s use of tone, pitch (does your child raise his voice when reading a question, for example?), and emphasis on certain words.. For example, I suspect you’ve all see this:

If one pauses after ‘eat’ as the comma signifies, the speaker is suggesting that the group eat to Grandma. If one omits the pause, thus ignoring the significance of the comma, the speaker is suggesting that the crowd actually EATS THE GRANDMA!

Note how the pitch would change if this were a question instead: Let’s eat Grandma????

Image in the pubic domain

How about Lynn Truss’ 2006 best seller Eats, Shoots, and Leaves? Many developing readers would likely enjoy reading this one. Ms.Truss emphasizes a “zero tolerance approach to punctuation.”

Image from Lori Josephson’s Library!

A reader’s oral vocabulary and language comprehension also play a role here. The more developed the reader’s oral vocabulary and language comprehension, the better able that reader will be to anticipate the words and the language structure–otherwise known as syntax. Fluent reading is generally thought to account for one-quarter to one-half or more of the differences in reading comprehension.

The ultimate goal of reading is to facilitate meaning. Meaning is compromised if the reader:

- has difficulty with the mechanics of word recognition; in other words, stops to ‘sound out’/decode unfamiliar words–resulting in reading so slowly as to lose meaning.

- omits and/or substitutes words.

- reads words inaccurately.

- reads words accurately, but ignores phrasing (does not pause at commas or stop at periods at the ends of sentences) or reads too quickly perhaps in a monotone voice.

Does your child read as described above?

Keep reading to learn about ways you can help your child improve their reading fluency!

Back to the original question. Why is this 9 year old reading 60 words per minute on their first or ‘cold read’? The teacher did not specify, but I suspect the culprits are all of the above to greater or lesser extents..

WHAT IS WPM? OR SHOULD IT BE WCPM?

Teachers measure fluency using the terms ‘WPM’ (Words Per Minute) or “WCPM” (Words Correct Per Minute). Parents are told their child reads ____ per minute. Are you confused by this number?

Let me simply explain.

DIBELS (Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills) is often used as a screener to measure ORF (Oral Reading Fluency) for grades K-8 (8th edition), and has been widely used since the mid-1990s. I well recall attending PD (Professional Development) in a small dank room in a church in NE Ohio to learn how to administer and score DIBELS! Other screeners are sometimes used; DIBELS is the most widely used.

A student is asked to read what would be considered 3 ‘grade level passage’ for 1 minute apiece. The teacher is to tally the number of words read and subtract the miscues (words skipped, added, mispronounced). The resultant number is the WCPM. If your child’s teacher tells you “Your child reads ___WPM”, go ahead and inquire if they mean WCPM. This is repeated in the fall, winter, and spring parts of the school year. Some children have their Oral Reading Fluency measured more often as needed–this is referred to as ‘progress monitoring’–that is to ‘monitor’ if ‘progress’ has been made.

Additionally (and hopefully), your child will be asked to ‘orally retell’ what they have just read orally. Your child should be able to orally tell you about 50% of the number of words they read orally in their retell summary (so if they read 100 words, the retell would be 50 words). Alas, many schools do not include this piece of the screening assessment. Red flags include:

- A child not recalling anything of what they read (a retell score of 0).

- A child beginning with the final sentence they read orally. This means the child is simply using short term rote memory rather than noting the main idea followed by details.

Try doing this exercise with your child(ren) you feel may have reading comprehension issues. If you have trouble counting the number of words in the oral reading sample and/or the retell, record your child reading orally, as well as the retell and count up the words and then play it back. This is easy to do on a cell phone.

Ask your child’s teacher about and pay attention to your child’s particular miscues (types of words missed, inserted, omitted, substituted):

- misreading high frequency common words such as: a/the, of/the, etc.

- leaving off word endings (i.e. “come” for “coming”).

- misreading the identical word many different ways.

- misreading longer, multisyllable words.

- omitting entire lines of text without realizing it.

These are also important red flags which may point to a reading issue.

Again, back to the original question. The teacher did not specify the types of errors the 9 year old made and did not comment on this student’s comprehension or prosody (reading with expression).

If you are thinking to yourself, “this is complicated”—you are 100% correct!

WHAT IS AN APPROPRIATE FLUENCY RATE FOR MY CHILD?

This is a complicated question to tackle totally dependent upon the strengths and weaknesses of the child in question.

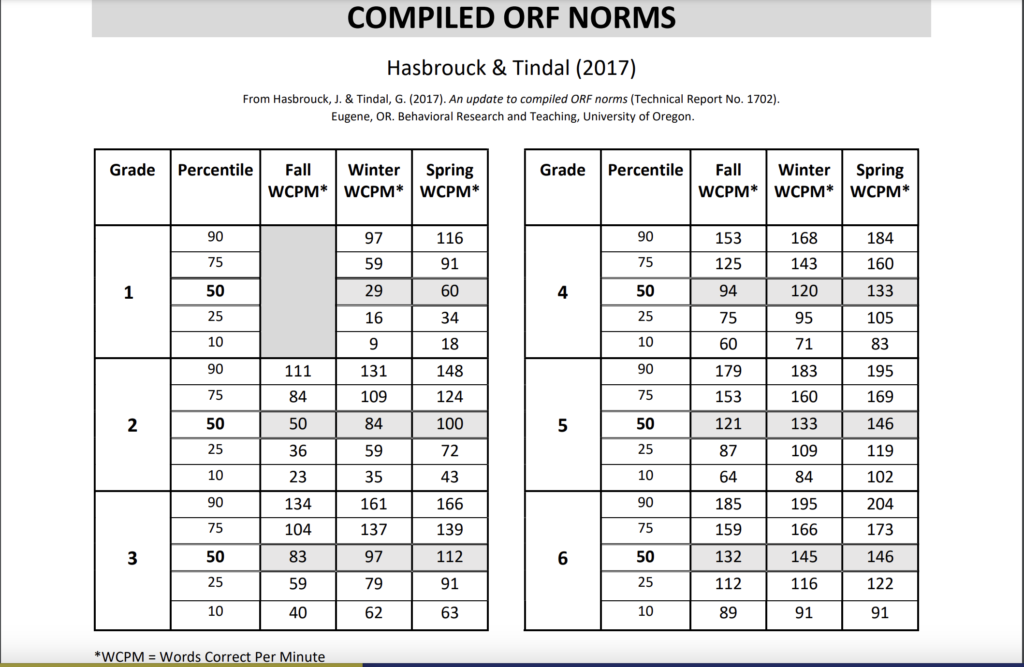

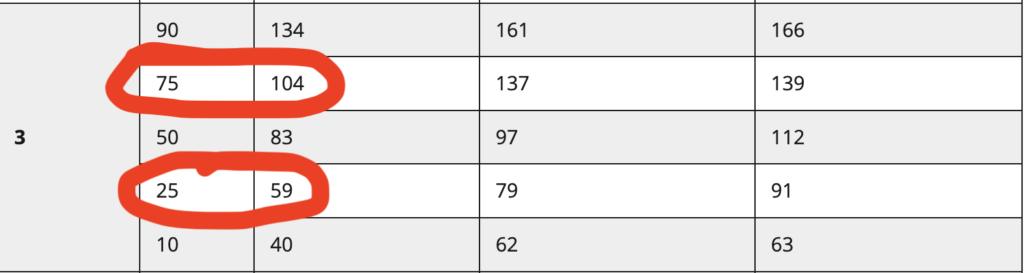

Let me say that the ‘Average Range’ encompasses a large fraction of the population–50% of it to be exact. ‘Average Range’ includes measurements between the 25th and 75th percentiles. So a student whose fluency is measured at the 25th percentile would be in the Average Range, as would one who scores at the 75th percentile with everything in between.

Here is Jan Hasbrouck’s fluency chart measuring WCPM, created (2006) and updated (2017):

So let’s say you have a 9 year old who is reading ‘at grade level’–if one administers the DIBELS using a 3rd grade passage, the ‘Average Range’ would be anywhere between 59 and 104 words if these passages were assessed in the fall of the 3rd grade year. Use the full chart above for reference to percentiles.

So…my questions to the teacher of the 9 year old…Was this student provided with a passage at grade level..or below grade level to accommodate for her/his dyslexia? 104 words would place this student at the 75th percentile according to the chart above. Is it necessary to continue working on fluency once a student achieves at the 50th percentile? Likely not. Reading is such a complex skill with so many variables that once a student’s fluency is at the 50th percentile, a lot of other skills would likely become a priority (vocabulary building, written language development, building background knowledge, etc.) and fluency practice is ill advised.

STRATEGIES AND TIPS TO HELP IMPROVE READING FLUENCY

According to my colleagues over at Reading Rockets, students scoring 10 or more words below the 50th percentile using the average score of two unpracticed readings from grade-level materials need a fluency-building program.

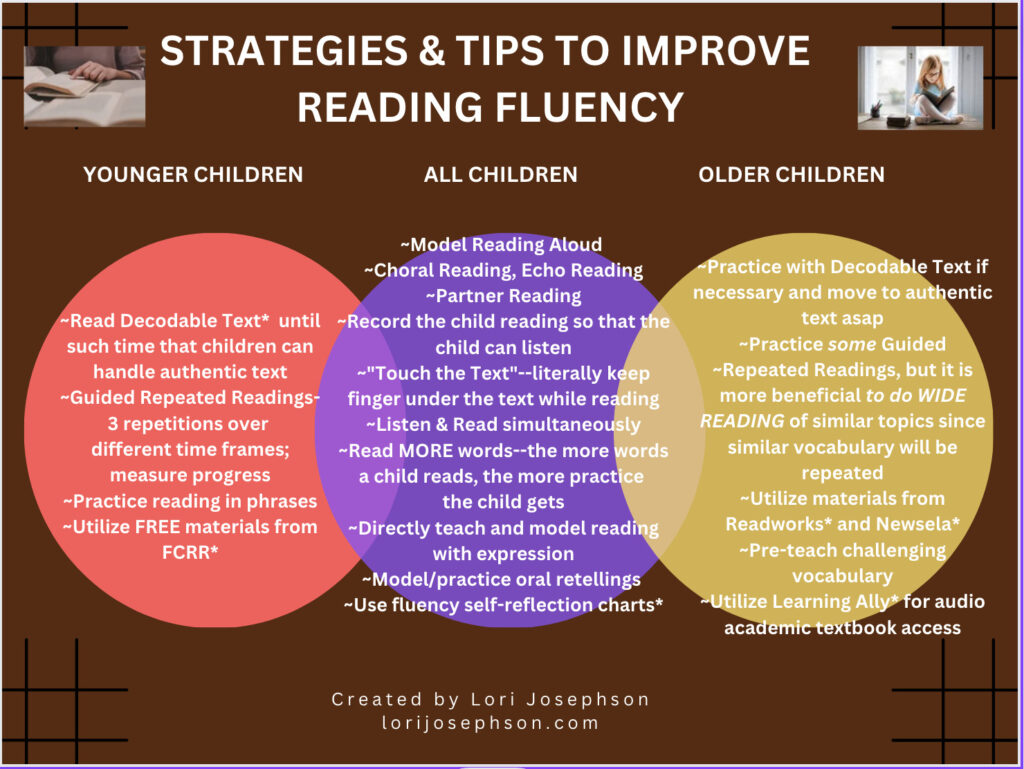

As you can see from the infographic below, it doesn’t really matter how old your child is if fluency practice is needed. Most of the tips and strategies are used for all children who would benefit from direct fluency instruction.

I refer to several materials, which have an asterisk (*) to the side. Here is a list of references:

*Decodable Text: books that allow for practice with taught sound/symbol relationships–such as short /ӑ/. Here is a list of decodables courtesy of The Reading League, many of which are free.

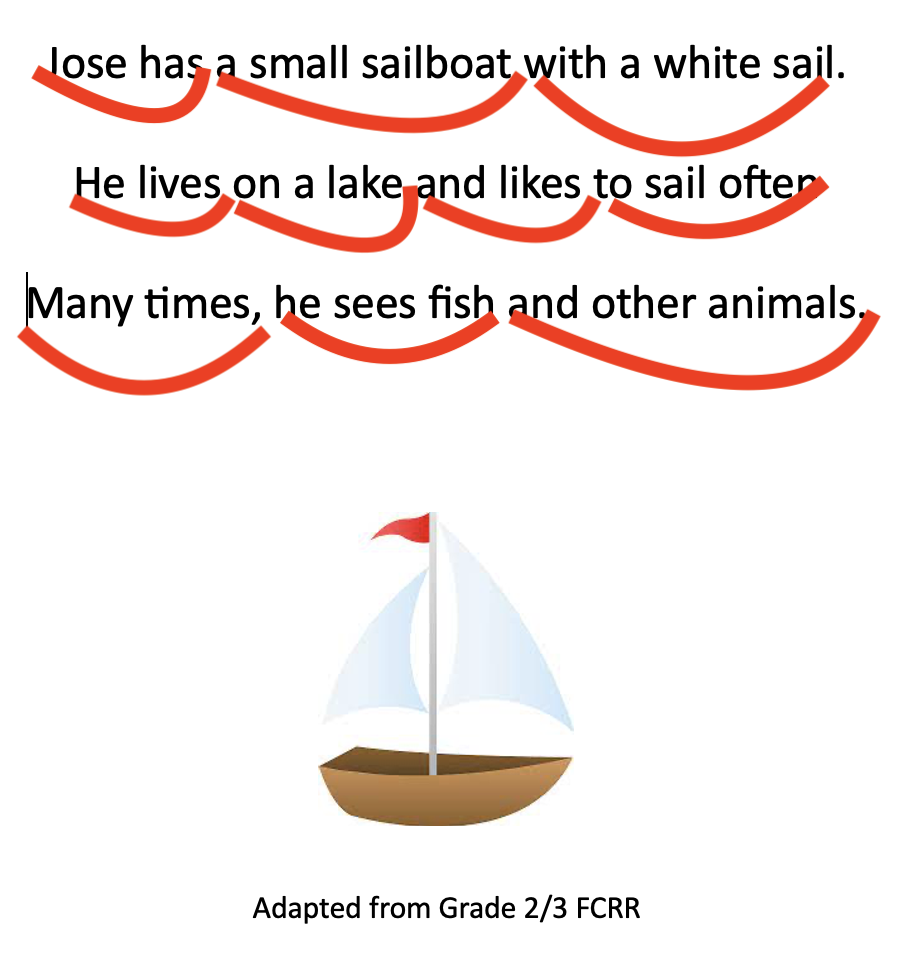

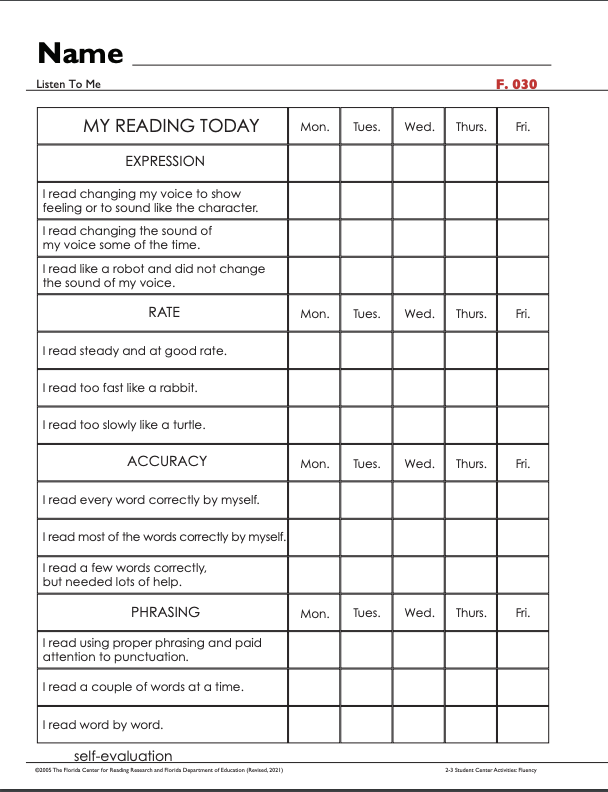

*FCRR: Florida Center for Reading Research has free materials for Grades K-5 targeting the 5 pillars of reading as per the National Reading Panel. Here are a sample of fluency practice exercises, as well as a sample self-reflection chart.

*Here you go for links to Readworks, Newsela, Learning Ally These sources are excellent when attempting to engage older readers in wide reading on a similar topic. Image from Readworks; there are many passages on each of these topics to choose from.

Remember, this process takes time and patience on the part of the adults working with the and the child. Talking to your student/child about what reading fluency is and why it is important are important parts of this process not to be neglected.

WHY IS IMPROVING FLUENCY SO CHALLENGING?

In my professional experience of several decades, working to improve fluency is the MOST CHALLENGING of all reading skills to improve–that is EVEN if they have pretty well mastered all the sound/symbol relationships, can decode and spell at grade level (and I mean all the way up to 12th grade!), and have well developed comprehension and written language skills.

IMHO, fluency (inclusive of reading with expression [prosody]) is “the last skill in…and then the last skill out.” Why?? I am unsure except to say that students who have slower rapid naming and retrieval skills have a more difficult time achieving fluency skills in the ‘Average Range’. These issues are precisely why students with dyslexia receive time extensions on high stakes tests such as the SATs, ACTs, as well as time extensions on in school tests. Do all adults you know read at the same pace? I don’t think so. Does every person who reads slowly have dyslexia? I don’t think so.

I do know this much–well developed fluency skills require a finely tuned orchestrated synchrony of sub-skills developed over time inclusive of the 5 pillars of reading as per The National Reading Panel (2000): Phonemic Awareness, Phonics (decoding), Vocabulary, Comprehension, Fluency, which are all interdependent as the human brain learns to read and spell.